Aquaculture Farmers and Recreational Users Tussle for Space Along Rhode Island’s Crowded Coastline

August 21, 2021

TIVERTON, R.I. — The Ocean State’s coastal areas and its salt ponds are some of the most popular, crowded and treasured spots in the state. They are recreational havens, economic drivers, and food suppliers.

Green Hill, Ninigret, Point Judith, Potter, Quonochontaug, and Winnapaug ponds run along Rhode Island’s southern coast. These ponds are coastal lagoons with shallow water that are separated from the open ocean by a natural barrier, creating a protected environment that hosts an assortment of wildlife and myriad activities. On any given day, especially in the summer, you can find people boating, swimming, paddling, tubing, kite surfing, fishing, and birding.

These ponds, as well as areas like the Sakonnet River and Nanaquaket Pond in Tiverton, have also become desired locations for aquaculture. These operations are particularly suited for salt ponds and coastal areas, because of shallower water, a longer growing season, and easier access.

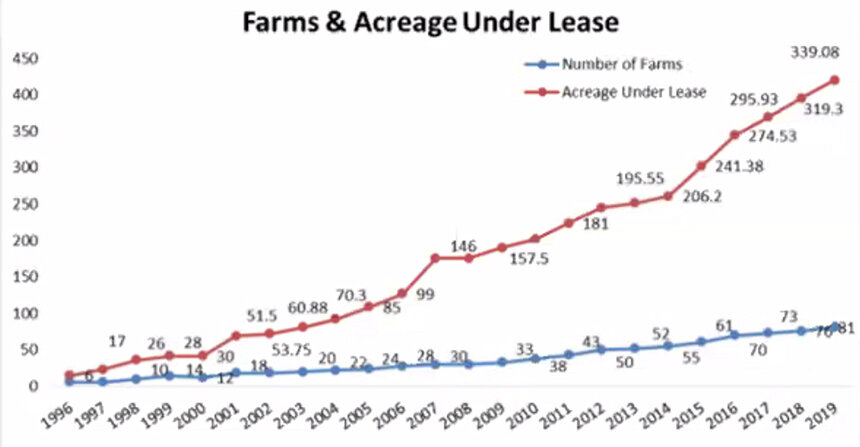

Rhode Island’s aquaculture industry has steadily been on the rise for the past two-plus decades. From 1996 to 2019, the number of aquaculture farms in Rhode Island increased from six to 81 and the amount of space they occupy, from less than 20 acres to nearly 340, according to information presented by Rod Hudson, a shellfish hatchery manager and adjunct professor at Roger Williams University, during an aquaculture discussion Aug. 12 at Tiverton Public Library. The event was organized by Rep. Michelle McGaw, a Democrat who represents Little Compton, Portsmouth, and Tiverton.

And while the general sentiment across the state, including by many who use the same waters to play, is that aquaculture is good for the local economy and environment — oysters like other bivalves filter water and remove excess nutrients such as nitrogen; the farming and harvesting of shellfish doesn’t require antibiotics and fertilizers; a small oyster farm can clean as much as 100 million gallons of water daily — resistance has become strong. Concerns have been raised that this intensifying interest in marine farming is eroding the proper management of aquaculture farm leases.

The Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) is the agency responsible for managing aquaculture leases. Under CRMC regulations, a maximum of 5 percent of a pond’s water surface area can be used for commercial aquaculture.

The application process includes site visits by the Rhode Island Department of Environmental Management (DEM), the Army Corps of Engineers, and the Rhode Island Historical Preservation & Heritage Commission. The application is also given a 30-day public notice period. This review determines if the proposal will be met with conflict, and the application is either approved or denied by CRMC’s aquaculture coordinator before the project is voted on by the 10-member board.

The agency’s current aquaculture coordinator, Benjamin Goetsch, told the Tiverton Harbor & Coastal Waters Management Commission at a meeting in March that CRMC doesn’t tell aquaculture applicants where to put their projects, saying the review process is designed to determine if a chosen site can accommodate such an operation.

The regulations and the application process are meant to provide structure for a growing industry, but it is Rhode Island General Law 20-10-1 that sets the foundation.

“It is in the best public interest of the people and the state that the land and waters of the state are utilized properly and effectively to produce plant and animal life,” according to state law. “The process of aquaculture should only be conducted within the waters of the state in a manner consistent with the best public interest.”

But what is in the public’s best interest is a matter of opinion. Aquaculture expansion is certainly positive, as the state is bringing back an industry that had its last boom at the turn of the 20th century. Tourism, recreation and commercial fishing are also important to the Ocean State, but when boaters, abutters, and fishermen have less access to coastal waters, tensions build.

Coastal property owners, recreational water users, anglers, waterfowl hunters, aquaculture operators, and state officials are grappling with how to navigate their way through a complicated situation involving a shared resource.

With Rhode Island’s aquaculture footprint growing, CRMC, during its ongoing effort to develop a Narragansett Bay Special Area Management Plan, “is holding robust discussions with an aquaculture working group and is looking hard at all of the processes involved in notifying, reviewing and deciding upon aquaculture applications for our public trust waters.”

Aquaculture can be a growing business if sites are chosen well, according to the Rhode Island Shellfisherman’s Association.

The East Coast Shellfish Growers Association recommends that growers, “Make a best effort to communicate early and openly with water-based and land-based neighbors about any facet of their operation which might affect them.”

User conflicts

Aquaculture projects proposed for the Sakonnet River in Tiverton have galvanized residents. Neighbors claim they did not hear about the two projects until they were well along in the CRMC approval process. This lack of transparency, they say, has made an already-contentious situation more problematic. They say the state’s notification process is lacking, ignores abutters and other water users, and needs to be revamped.

However, unlike municipal zoning and local land-use issues, abutters are not required to be notified by CRMC or DEM of aquaculture operations proposed for state waters.

Kenneth Mendez, who has owned a home on Sapowet Marsh for the past three years, is among those concerned about plans to put more oyster cages in a Tiverton waterbody popular with the public. Two existing aquaculture operations on the eastern shoreline of the Sakonnet River take up about 5.5 acres in Tiverton’s riparian waters.

In a June 11 email to the DEM director, Mendez expressed concern that there is a lack of public notice when it comes to hearings associated with aquaculture projects. He said this lack of notification can potentially impact the outcome of important votes.

CRMC noted it has created an online listserve for anyone who wants to be notified of any activities related to Rhode Island aquaculture. The agency also has a webpage devoted to the industry.

To address residents’ concerns, the Tiverton Town Council recently directed the town solicitor to look over a proposed resolution that, if passed locally and sent to the General Assembly, could give residents more time to respond to aquaculture proposals than state regulations currently require.

The resolution was reportedly put on the agenda by council member Jay Edwards. He has expressed concern about the way CRMC has dealt with the aquaculture farms proposed to the north and south of Sapowet Point on the Sakonnet River.

The proposed Bowen oyster farm plan — the one south of Sapowet Point and near where Sapowet Marsh empties into the Sakonnet River — was submitted by Little Compton brothers Patrick and Sean Bowen. Their application seeks CRMC permission to submerge up to 200 oysters cages in a 0.95-acre area 285 feet offshore.

The farm would be the Bowens’ first dabble at running an aquaculture operation. Patrick, who teaches at the Diman Regional Vocational Technical High School in Fall River, Mass., and Sean, who is the aquaculture coordinator and composting coordinator for the Massachusetts Department of Agricultural Resources, told ecoRI News the operation would start small, with 30-40 cages. Perhaps in five years the farm would ramp up to the maximum 200 cages, they said.

As for claims the public wasn’t made adequately aware of the project, the lifelong Rhode Islanders said seven public hearings have been held on their proposal, the comment period was extended by 15 days, and their application has been posted on the websites of CRMC and the town of Tiverton. The brothers noted they have changed the farm’s plan three times to address residents’ concerns.

The Bowen aquaculture plan was originally filed in December 2019 and was expected to come to a CRMC board vote in June, but pushback from opponents, including Mendez, Rick Metcalf, Clint Clemens, and Donald Libbey, delayed the process.

The project’s opponents have since launched a website and posted signs up and down Seapowet Avenue urging the preservation of access rights to the popular waterway.

Mendez, who regularly fishes for stripers and blues in the area where the Bowens’ oyster cages would be submerged, told ecoRI News the farm would encroach on a public trust.

Metcalf, an avid Sakonnet River kayaker whose property overlooks the area where the Bowens have proposed their aquaculture operation, said DEM’s nearby Sapowet Marsh Wildlife Management Area parking lots are packed Saturdays and Sundays with people boating, fishing and swimming in the tidal waters behind his house.

In a June 22 email to CRMC about the two Sakonnet River aquaculture projects, Libbey, a Neck Road resident, wrote that while “we can appreciate that this use seems compatible with the area, it is not.” He said both locations are heavily used by recreational boaters, swimmers and anglers and their free flow of navigation would be interrupted by the aquaculture operations.

In another late-June email to CRMC, in regards to the Bowen aquaculture proposal, Peter Jenkins, owner of a Middletown-based saltwater fishing store and a member of the Rhode Island Saltwater Anglers Association’s Access Committee, wrote that the proposed site would “unreasonably interfere with, impair, and significantly impact existing use of tidal waters. There are few waters in Rhode Island that are as safe and as accessible as this area for recreational anglers who wade fish.”

Sean Bowen, who graduated from Unity College in Maine with a degree in sustainable aquaculture, called the claims the operation would interfere with recreational uses misleading. He noted the 16-inch-high cages would be submerged, four buoys would mark the farm’s perimeter and the cages would be placed in rows of 10, with 25 feet between each row. He said kayaks and paddleboards would be able to pass over the cages. He said there would still be plenty of room to fish.

“We want a low-profile operation with a low-carbon footprint,” Patrick Bowen said. “We want to be invisible.”

Tiverton resident Will Miranda is concerned about the impact the growing number of Rhode Island aquaculture operations are having on commercial fishing. While not a commercial fisherman himself, his father and other family members are, and he believes aquaculture farms can make valuable fishing and wild shellfishing areas inaccessible.

“They’re going up everywhere and anywhere,” he said. “We need to find suitable places to put them, but it seems like there is no plan for where they can be put. They should be going in places that have minimal impacts on the community.”

Miranda is also a kite surfer, but the 38-year-old doesn’t believe aquaculture, at least when it comes to his recreational use of salt ponds and coastal areas, hinders his enjoyment.

“I could get tangled up in cages and buoys and fall, but that’s my problem,” he said. “That’s on me.” He said floating cages are the bigger problem for a kiteboarder.

The New England chapter of Backcountry Hunters & Anglers has said the impacts to hunters’ use of the Sapowet Marsh area have not been acknowledged, considered or addressed.

The Boehringer aquaculture application, submitted in January by Wakefield residents Brad Boehringer and Travis Lundgren, requests the use of floating and submerged gear to raise oysters and scallops in a nearly 3-acre site north of Sapowet Point.

A similar situation is playing out in South Kingstown, where a proposed 3-acre expansion of an aquaculture operation in Potter Pond’s Segar Cove has received pushback. Neighbors are concerned the project would effectively privatize more of the pond and further limit public access. Potter Pond currently features about 9 acres of aquaculture.

Like in Tiverton, opponents have created a website, made CRMC aware of their disapproval, and hired attorneys.

The Sakonnet River applications are currently under review and therefore CRMC can’t comment on them directly, according to Laura Dwyer, the agency’s public educator and information coordinator.

She noted the Potter Pond project still needs to go before the CRMC board for consideration. In an early August email, she said the board is waiting on scheduling and a written recommendation from a subcommittee.

“Regarding aquaculture generally, the CRMC has always sought to balance the many uses of our coastal ponds and Narragansett Bay, of which aquaculture is one,” Dwyer wrote. “However, CRMC evaluates each application it receives on its own merits, and also considers what the impacts of these proposed activities may be with the many recreational, commercial, and other uses and users of the state’s Public Trust waters.”

No one at CRMC was made available to speak about the growing demands being put on Rhode Island’s salt ponds and coastal areas and how this space is being managed. The next CRMC board meeting is scheduled for Aug. 24.

Thank you for a balanced article on the subject of Oyster Farming in RI waters. What the majority of the public wants is a fair and transparent process that allows for valuable public input. That is not the process with CRMC today, which is why the recent appointment of a Committee of legislators and stakeholders to discuss revamping CRMC is so important.

What else is important, is completing the SAMP process, which hopefully will determine where aquaculture should be located in the waters of RI. When the historic use of the many to RI’s waters are superseded by the commercialization of the Public Trust by the few, the system is flawed and should be revamped. Until such time as those changes are instituted and the SAMP program is finalized, there should be a moratorium on approval of any aquaculture projects.

i m a member of the shellfish advisory committee which preliminarily reviews aquaculture applications and sends a recommendation to the marine fisheries council which then sends a recommendation to CRMC. i m also on the committee to advise CRMC on the aquaculture portion of the Bay SAMP.

i ve been complaining about the inadequate and un-rigorous public notification for years. its true that the applications are listed on the CRMC website and one can be notified via the aquaculture listserve however that begs the question first of who’s hobby it is to peruse the CRMC website and second how is one supposed to know to sign up for the listserve. by the way even if one was on the listserve are they supposed to review the listing regularly to see if an application will effect them. the complaints by Bay users, lets call them stakeholders regardless of what type of user they are (other commercial entities or private citizens) has increased dramatically with the increase in applications.

as frank points out, other state and municipal regulatory processes (zoning board applications, septic system variances for example) have required abutter notifications via direct contact (certified letters) . the applicant is responsible for the notification which has to be documented to the regulatory agency. there is no such requirement for aquaculture applications which leads to growing conflicts that this article highlights. presently the CRMC Type I water definition includes preservation criteria which is being ignored with the granting of some of these leases. hopefully the SAMP aquaculture process will formulate a formal abutter notification process for both water users and upland property owners and not leave it up chance as to whether or not a potential effected party becomes aware of an application

dick pastore

Rhode Island has 400 miles of coastline, the area of leases is 340 acres, about 1/2 square mile. This case goes to show just how little of the 400 miles is actually prime habitat and/or accessible to the public . Hence the conflicts over use.

I would hope that in a fair and democratic society that we need to hold our government officials accountable to live up to their commitment to the people they serve. It seems to me that aquaculture, although an important enterprise in our state, makes up a modest contribution to RI’s revenue and employment base. Therefore, a thoughtful, long-range modernized plan for our coastline and wetlands, including scientific impact studies of aquaculture, not just comments like "well, oysters clean the water" seems to be warranted.

My understanding is that once these leases are granted access rights-for all intents and purposes-are given up FOREVER since the leases can be sold. And that "forever" is a HUGE price to pay for lost access, potential and real hazards to novice or injured water enthusiasts, and unstudied long-term damage to our precious ecosystem, not to mention unsightliness of these farms and/or noise pollution by any cleaning equipment. Please check out saveseapowet.org for the latest updates. Thank you

Mr. Gerritt’s aquaculture proportions are spoken in the same jargon used by the aquaculture advocates. It disregards spatial planning, shellfish disease introductions, genetic dilution of wild stocks, localized sediment impacts, bird roosting on gear, displacement of public trust usage, and more, all in exchange for a nominal annual fee. Those concerned with these impact little if any recourse.