Common Good Preached to Help Protect Vulnerable Waterfront Neighborhood in Portsmouth

June 28, 2021

PORTSMOUTH, R.I. — Among those working to prepare an at-risk coastal area to the impacts of a changing climate are a neighborhood newbie, a veteran and a lifer. They recognize their waterfront community is stressed.

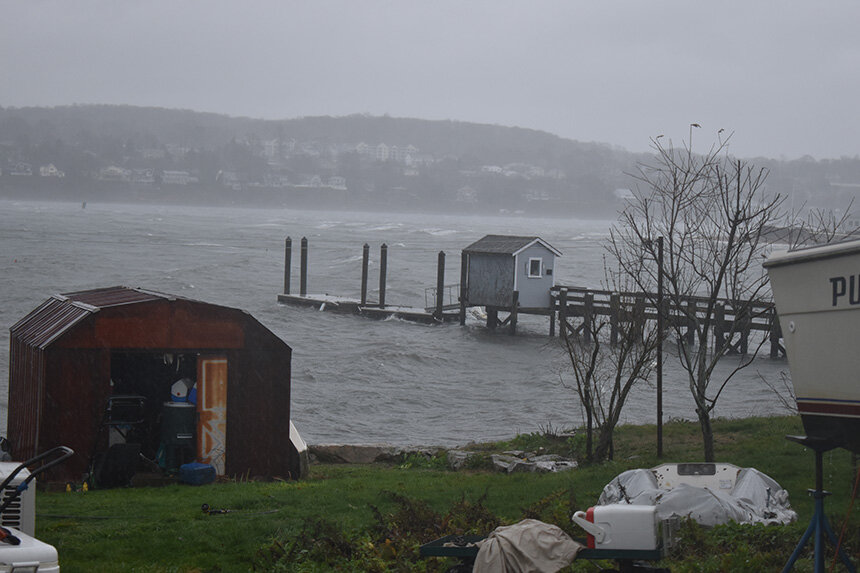

Should, say, a Category 3 hurricane hit, many Common Fence Point residents understand where they live, a peninsula that juts into Mount Hope Bay, is “ground zero as one of the most vulnerable shorelines in the state,” as David Vallee of the National Weather Service told them early last year.

The last Category 3 hurricane to hit Rhode Island was Carol in August 1954. The storm hammered Common Fence Point. Diane Barrette and her family, which has had a presence here since 1922, were there to witness it. She said no warning was given, and then State Police arrived and began to evacuate people. She and her family got out just in time.

“Luckily, we were probably one of the last cars that got over the Stone Bridge before it broke,” said Barrette, who, since retiring in 2008 from teaching, has made Common Fence Point her year-round home. “My father had been in Newport [at work] so he came as far as the Mount Hope Bridge, which was closed because of the wind. He could see a house floating down the river but he didn’t know if we were safe or not. It wasn’t until 8 or 9 o’clock that night that he was able to reach us.”

Carol washed most of the Stone Bridge away. The 47-year-old bridge was replaced in 1956 by the Sakonnet River Bridge, which was under construction at the time Carol arrived two years earlier.

Barrette has two vivid memories of Carol’s visit — beyond getting over the Stone Bridge before it collapsed and the amount of wood, from a lumberyard across the way in Tiverton, that was thrown about the neighborhood: what happened at a neighbor’s house and what almost happened at her house.

“The house across the street from where we were sits on a knoll — it was actually a judge in Fall River [Mass.] that owned it — and they had delivered two bottles of milk in the morning. The house was gone but the bottles of milk were still there,” she recalled. “And we had a cabin cruiser that broke its mooring from Tiverton and came across and landed on the back steps of the house. The chain, anchor and mooring had wrapped around a big chestnut tree we had out in the backyard, so that prevented it from knocking down the house.”

With that historical point of view, Barrette and her husband, Paul, who live on a slight hill on Anthony Road in a house that is about 16 feet above sea level, are concerned about storm surge and coastal winds generated by more frequent and intense weather events.

Their concerns are shared by many, but not all, in a densely populated neighborhood — there are nearly 700 houses, some of them of second homes — that is vulnerable to the impacts of a changing climate, most notably accelerated coastal erosion and sea-level rise.

Across the street from the neighborhood’s public center, the Common Fence Point community hall on Anthony Road, is a ball field that was dedicated in 1968. The field now regularly floods during storms and high tides, especially as the high-tide watermark slowly creeps up. Parts of it are no longer mowed, to allow coastal wetlands to retreat from rising seas and to better protect the neighborhood from flooding.

Jeff Prater moved to the neighborhood four years ago from Florida, where he and his family rode out about a dozen hurricanes. He said planning and preparation are key. Since “the number one thing” in Common Fence Point is the coastline, he said much of the neighborhood’s preparedness needs to address climate change, sea-level rise and storms. He’s worried about complacency.

“My concern is for those that do not realize the changing landscape and are not proactive in mitigating the risk,” he said. “What we’re doing here with our preparedness committee and with shoreline erosion preservation is how you plan for the changing climate. We can’t have people ignoring what needs to be done. We need to have a plan on how we are going to deal with climate change.”

Kary Miksis and her husband, Chuck, became frequent neighborhood visitors in 2003. Their second home became their only home nine years later. She and her husband are concerned about shoreline erosion and sea-level rise, especially along Common Fence Common Fence Boulevard, where they and the Praters live. She agreed with Prater that the neighborhood needs to be proactive when dealing with the many challenges presented by climate change, not reactive.

“It’s a constant battle when you live in a place like this,” Miksis said. “Do you preserve nature or do you worry about your view, because many people down here don’t understand that the trees, the hedgerows and the weeds they are actually part of the view.”

All three residents are members of the Common Fence Point Preparedness Committee. The group’s mission is to help all of the neighborhood’s residents better understand how they can take action to protect themselves, their homes and the close-knit community from severe weather and other challenges presented by the climate crisis. The committee is stressing education and awareness.

“We want to educate them on the issues so we can take action,” said Prater, noting that engaging neighbors in conversation is important.

Among the areas of concern for the committee and its working group — of which Barrette, Prater and Miksis are members — are shoreline erosion along Common Fence Boulevard; stormwater runoff from Anthony Road that continues to feed an explosion of phragmites around a pond, once popular for ice hockey; the aforementioned flooding of Thomas F. Kennedy Memorial Field; and the narrowing of an inlet in the western corner of the peninsula that has restricted the flow of water and damaged a salt marsh that has already been restored at least once.

Prater said the site wasn’t maintained and the problem has been exacerbated by people who have placed rocks in the inlet to get to the other side. As the amount of fresh water builds up in the detention pond, he noted the amount of invasive plants increases.

The property along the shoreline of Common Fence Boulevard is owned by the Common Fence Point Improvement Association, which owns multiple parcels on the popular peninsula, which, especially in the summer, can be crowded with out-of-state license plates.

To help build back the eroding buffer, the town of Portsmouth, nearly three years ago in a one-shot deal, put rocks along the shore. Wenley Ferguson, director of habitat restoration for Save The Bay, directed the Common Fence Point Preparedness Committee to introduce, among the recently placed fortification, deep-rooted plants that wouldn’t grow high and block water views.

The Common Fence Boulevard shoreline was partially destabilized three decades ago when one of Miksis’ and Prater’s neighbors hired a bulldozer to excavate the vegetation across the street from his house to create a beach. He then had some 10 truckloads of fine sand delivered, which, he told Prater, washed away in about eight weeks. The area is still recovering from the costly assault.

The Improvement Association, which has a membership of some 125 residents, also owns the soggy ball field. Barrette, for one, would like to see the property put to better use. The playground, like the community hall on the other side of Anthony Road, is used by the YMCA as part of its after-care program. Barrette visions, in the dry areas of the property, tennis and pickleball courts and a basketball court. She said let nature reclaim the parcel’s low-lying areas, where mowing has already been cut back. She’s hoping the site is a future Coastal Resources Management Council (CRMC) restoration project.

In fact, the simple act of cutting — and planting — of vegetation is a community challenge. Prater noted trees and wetland buffers have been chopped down to improve water views. On the opposite end of this problem, he said, are those who have planted vegetation in the neighborhood’s eight shoreline public-access points. (There’s the related problem of litter left behind by some of those who access these rights of way.)

The neighborhood committee has spent the past three years working with the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Resources Center, the Narragansett Bay National Estuarine Research Reserve (NBNERR), the Rhode Island School of Design and the town of Portsmouth, among others, to help educate their fellow residents and encourage their involvement in efforts to better protect where they live.

Pam Rubinoff, of the Coastal Resources Center, NBNERR’s Jennifer West and Janet Freedman from CRMC, who retired in February, led a webinar in early October of last year to educate residents about sea-level rise, stormwater runoff and flooding.

Among the information the trio shared was the importance of living shorelines, to help reduce wave action and slow erosion. They noted a 15-foot-high wall would need to be built to keep a big storm from battering the peninsula.

In light of these facts and other climate realities, the Common Fence Point Preparedness Committee’s goals are to connect neighbors and respond to their needs, share pertinent information and resources, promote community preparedness and build resilience. It also has tasked itself with better understanding residents’ concerns.

Committee members worked with RISD to gather community input on issues of sea-level rise and storm vulnerability. This work centered on the impacts of modest levels of sea-level rise on marsh areas and infrastructure in Portsmouth neighborhoods, including Common Fence Point.

Some 2 miles away in the Island Park neighborhood tides already flood storm drains on Park Avenue several times a year. With 3 feet of sea-level rise, Park Avenue will be gone.

The Common Fence Point Preparedness Committee wants its neighborhood to be — well, its name says it all — prepared for climate changes, because, as the kind of flooding Island Park is experiencing becomes more frequent, it will increasingly impact road access and the viability of septic systems in low-lying areas, of which Common Fence Point is one. There’s also other concerns.

“There are requirements and there’s a reason why we have these requirements,” Prater said. “You just can’t put something anywhere, because if you get a big storm that comes through and it becomes a hazard it could knock into someone else’s house and cause damage. Those building requirements are there for a reason.”