Infighting Over Genetic Engineering Splinters Efforts to Save the American Chestnut

Is a genetically engineered tree the only way to save the American chestnut? Or is this method, as its detractors allege, a Trojan horse to get genetically modified trees through the regulatory process to allow companies with interests in biomass to create large-scale, artificially altered tree farms?

July 31, 2020

“This is where the will to grapple with our hard and pressing environmental problems begins: in relationship to something other, that you love beyond any utility, beyond any logic.” — Susan Freinkel, “American Chestnut: The Life, Death and Rebirth of a Perfect Tree”

SOUTH KINGSTOWN, R.I. — What would you do to save something you love? How far would you go?

The passion that pushes the legions of volunteers in their mission to save the American chestnut borders on fanatical obsession. Since 1983, members of The American Chestnut Foundation (TACF) have dutifully cared for, bred, and attempted to restore a tree that was once the pride of U.S. woodlands before blight decimated the species.

In the nearly four decades since the Asheville, N.C.-based organization was founded, another quest for the tree’s redemption has been running concurrently to TACF’s backcross breeding program. It has the same aim, but employs different means.

It has various names: transgenic tree, OxO tree, genetically engineered tree. But the premise is the same: Play God, and then pray to God it works.

The quest for a genetically engineered American chestnut, a chestnut to save them all, has torn the community asunder. Proponents on all sides — a team of researchers who pioneered the insertion of a wheat gene resistant to blight into the American chestnut; a husband and wife duo who resigned from their positions in their local TACF chapter in protest of the transgenic tree; and a volunteer who dutifully carries on her work crossbreeding Chinese and American trees — hope that their method is the truest, the surest way to bring back the inimitable American chestnut tree.

But the truth is, no one really knows.

Volunteer effort

“Watch out for that poison ivy,” said Yvonne Federowicz as she unfastened a heavy chain linking a worn post to a gate. We’re in South Kingstown, home to beaches, farmland, and orchards of American chestnut hybrids. “Now, pull your car through and then we’ll take you to the first orchard.”

Federowicz has been a member of the Rhode Island/Massachusetts chapter of the TACF since 2001, working with a group of other volunteers to restore the keystone tree species to its pre-blight glory.

The method they and other TACF chapters — save for the New York one — use is called backcross breeding. It involves taking blight-resistant Chinese chestnuts and crossing them with American chestnuts. The crossing goes onward (or, backwards?), backcrossing again with another American chestnut until a tree that is about 94 percent American, but with blight resistance from its Chinese ancestors, is created. Current plans include using the most blight-resistant trees at other locations to further grow and diversify wild chestnut populations.

“There are two orchards here in South Kingstown, on land owned by the South Kingstown Land Trust — we’ve worked with them and the URI master gardeners. It’s a wonderful collaboration,” Federowicz said as we coat ourselves with bug spray, then head over to the cluster of American chestnut trees shimmering to our right.

“This was the first orchard we planted here,” said Federowicz, as she examined a serrated leaf. “The other orchard is a bit bigger.”

The trees here are a little wilted, the soil not as balanced as the orchard over yonder.

We drive over to the second orchard, which is large and lush. Rows of younger chestnuts stand sentinel near the entrance, while more mature trees, including Chinese and hybrid varietals, create their own canopy. Federowicz walked through a break in the plantings and pointed out where she and the other volunteers inoculated the saplings with the blight — aka the fungus Cryphonectria parasitica.

“You can see here how this tree didn’t have much resistance to the blight,” she said, squatting down to examine a rust-colored, rotten section of a tree. We amble over to a Chinese chestnut that had also been inoculated. It’s a healthy-looking piercing.

“Not only does it have resistance to the blight, you can see it’s shorter, squatter, and its leaves are broader and a bit fuzzy,” said Federowicz, picking off a leaf and handing it to me.

Federowicz examined the trees’ trunks and leaves and talked factoids about the incredible, edible nut and the sad (but redemptive) story of the tree that bears it.

Majestic species

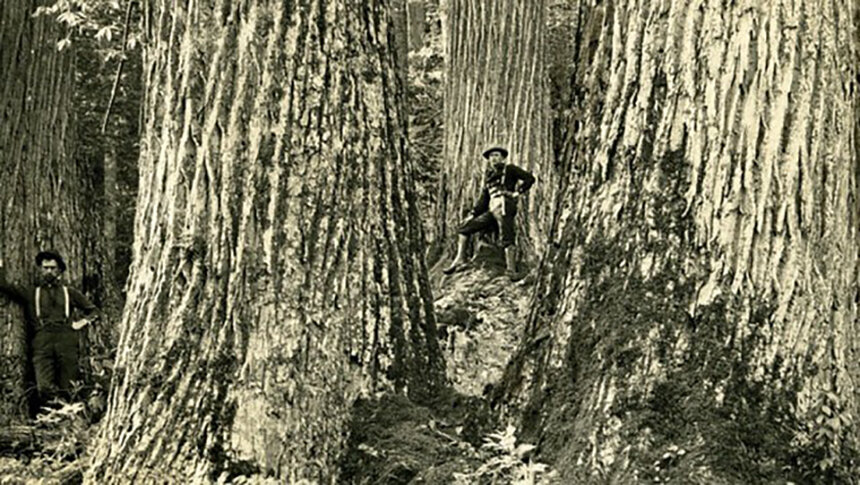

The American chestnut, above the pines and spruces, the hemlocks and birch, above even the mighty oaks and maples, inspires a sense of nostalgia that reaches deep into the American psyche.

“The story of the tree was all around me,” Federowicz said. “I grew up in western Pennsylvania, going up to my grandmother’s house on Chestnut Ridge. You start noticing, once you look for it, that there are so many chestnut streets, chestnut hills, so many things named after it. It was a very dominant tree species.”

Indigenous people revered the nut, which unlike its oak cousin’s acorns, didn’t need much in the way of processing. One story, Hodadenon and the chestnut tree, tells the tale of a magical supply of chestnuts, and calls the nut a sacred food to be shared with all who wanted them.

Appalachian settlers also took to the tree with its plentiful fruit, sturdy, rot-resistant wood, and tall, domineering form. It was a means of food and a means of income for many.

But when a fungus from East Asia was carried to the United States in 1904, the most American of American trees was devastated. More than 4 billion trees were ravaged by the blight, and today, few mature trees still stand. Saplings live a particularly feeble existence, sprouting up from the stumps of their dead relatives, growing to a certain age, then dying from blight before they have the chance to mature.

Since the blight was first introduced, arborists and lovers of the American chestnut have battled Cryphonectria parasitica with the fury of a mama bear. States formed commissions dedicated to saving the tree, and one newspaper from Honesdale, Pa., implored its woodsmen, “burn that tree; spare not a single bough,” referring to trees infected by the blight.

Then, in 1983, TACF was born in an effort to breed a blight-resistant American chestnut. The organization planted its first orchard six years later. The method it embraced was backcross breeding, the same program that Federowicz and the RI/MA chapter use on the orchards in South Kingstown.

And for a time, this was enough.

But unknown to many of the members in the organization’s 16 chapters, who spent their days in cherry pickers hand fertilizing trees to get closer to blight resistance, a group of residents and scientists in Upstate New York were looking at different techniques to save the tree.

Altered approach

Herbert Darling tried to save the mature chestnut tree growing on his property in western New York. He tried so hard that he even rented a helicopter and fired shotgun shells filled with pollen from male blossoms on a nearby tree onto it, hoping they would mingle and produce nuts he could plant.

But when his fantastical efforts produced no fruit — the tree died from blight years later — Darling turned to William Powell and Charles Maynard at the State University of New York College of Environmental Science and Forestry (SUNY-ESF) for help.

“I had worked with chestnuts before,” Powell said. “I came here, and I teamed up with Dr. Maynard who is a forestry person, and what happened was, in 1989, a group that had formed a New York chapter of TACF came to us at our campus and they wanted to take a different approach than what the national group was taking.”

Darling and friends tasked the scientists at SUNY-ESF to create a genetically modified tree resistant to blight.

“The people who came to us wanted to try a more modern techniques,” Powell said. “They wanted us to try and do genetic engineering. And since I had a background in molecular biology and fungus, and Dr. Maynard had a background in tissue culture and forestry in general, we got together and said, ‘Well, we could do that.’ So, it really was started by the public asking us to do this.”

Once they got Powell and Maynard on board, the New York chapter of TACF gave no more than a glance beyond its state borders at the backcross breeding program being used by other chapters around the country.

“Every year we have meetings with the New York chapter and keep them updated, and they gave us funding to pay for grad students, stuff like that, to work on this,” Powell said.

New York became the womb of the genetically engineered chestnut tree program, with Powell, Maynard, and assorted graduate students in gestalt for 30 years as they plucked and poked at the genes of the American chestnut, trying to find a way to make it resistant to the blight.

It wasn’t until the mid-1990s that Powell found something that just might do it. A post-doc student had returned from a plant physiology conference, and she gave Powell the book of abstracts. Tucked away in it was an idea that caught Powell’s attention.

“I saw this really neat abstract where someone was taking this gene from wheat, this enzyme call oxalate oxidase (OxO), and putting it into tomatoes and a few other plants and making them resistant to fungal pathogens that make an acid called oxalic,” he said. “And because of my background in hypervirulence, I realized that’s what the virus does to the fungus too, it stops it from making this acid, and so the idea was, ‘Wow, if I can get this enzyme produced in the tree, then it’s gonna get rid of this acid and possibly the tree can survive.’ And so that was the eureka moment. So we started the long process of getting that wheat gene into the tree. It only took us twenty-some years (he laughs) but it was successful.”

Today, the OxO tree is waiting approval from the Food and Drug Administration, the Environmental Protection Agency, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. If approved, the transgenic American chestnut could become the first genetically engineered tree approved for planting in the United States. (There are other genetically engineered trees making their way through the approval process, such as a genetically modified, freeze-tolerant eucalyptus tree.)

But as Powell and his colleagues wait for a federal decision on the OxO tree, a storm has been brewing in the chapters of TACF between proponents of the transgenic tree and naysayers that fear it will change the way forests are managed and planted.

Tree fork

Lois Breault-Melican and her husband, Denis Melican, practice what they preach when it comes to chestnuts.

“People think of chestnuts as, ‘Oh, people roasted them at Christmastime because of the song,’ but actually chestnuts are one of the most interesting and utilitarian natural foods that exists,” Denis said. “All nuts are good for you but they’re usually 60 to 80 percent fat, but the chestnut (he pauses) the chestnut is only 5 percent fat.”

He noted that his wife makes a mean version of pan-roasted Brussels sprouts with bacon, maple syrup, and chestnuts. He said she uses chestnut flour to make almost-guilt-free brownies.

The couple first fell in love with the American chestnut tree 20 years ago during a walking tour.

“Denis and I both worked for the Massachusetts state parks system, and we were doing a Sunday afternoon walking tour, and someone on the tour said, ‘Hey, did you ever hear about the American Chestnut Foundation?’” Lois said. “And she went on to tell us how they were restoring the tree. That night we looked it up online and were fascinated and thought this was a great idea and went to a couple of meetings, and then joined the foundation because we thought it was a great project.”

During their time as TACF members, Lois and Denis were part of the team that planted the first chestnut orchard on Massachusetts state land, at Moore State Park in Paxton, and they became board members. Throughout their tenure, they planted 233 trees at Moore State Park and helped create and maintain orchards as far west as the Berkshires.

“We have a lot of experience, watching with our own eyes and caring for thousands of chestnut trees that went through the growing process,” Denis said.

They were friends with Federowicz, who described them as “two people who are excellent at outreach, and they love chestnuts.”

That is why it hurt so badly when the couple left the Rhode Island/Massachusetts chapter of the TACF in a very public way in protest of the transgenic tree.

In a letter dated March 28, 2019, Lois and Denis submitted their resignation from TACF. In it, they wrote, “Because of our opposition to the genetically engineered chestnut, Denis and I have come to the sad conclusion that we can no longer serve on the MA/RI Chapter board of The American Chestnut Foundation. Therefore, I will also resign as chapter president. We are unwilling to lift a finger, donate a nickel or spend one minute of our time assisting the development of GE trees or using the American chestnut to promote biotechnology in forests as any kind of ‘benefit’ to the environment.”

The letter and their resignations came as a response to TACF’s national headquarters accepting the validity of the transgenic tree and stating that it would be integrated into the organization’s breeding program upon federal approval.

“We’re taking a three-pronged approach with breeding, biotech, and biocontrol,” said Kendra Collins, science coordinator for the TACF New England Region. “All of those programs have merit, all of them need volunteers to work on them. For most folks, whatever will save the species, that’s the goal, that’s what they’re excited about.”

TACF has decided to put its chestnuts in the biotech basket, with backcross-bred trees kept as a way to bring biodiversity to the transgenic crop.

“If federal approval is granted, TACF plans to breed transgenic tree with wild trees over multiple generations to dilute out the transgenic founder genome and increase the genetic diversity of the blight-tolerant population,” according to the TACF website.

For many, the OxO tree is a way to resuscitate a keystone hardwood that will increase biodiversity, something the world’s forests sorely need.

To understand why Denis, Lois, a Buffalo, N.Y.-based activist group, the Global Justice Ecology Project, and others oppose the transgenic tree requires diving into the murky waters of the international lumber trade, tree plantations, and the project’s funding sources.

Green desert

A recent article in The New York Times Magazine about the transgenic tree noted that for most of its life, the SUNY-ESF project to create a genetically engineered American chestnut was a “shoestring operation” until a recent $3 million donation from the Templeton World Charity Foundation.

Anne Petermann, executive director of the Global Justice Ecology Network, doesn’t agree. She even co-authored a 2019 white paper on the subject.

“The corporate support has been on multiple levels, and the reason that the researchers are able to say that they don’t get much money from corporations is because a lot of money has come through consortia,” she said. “For example, the Forest Health Initiative gave Powell’s work more than a million dollars over eight years. The FHI includes Duke Energy, so Duke Energy was a major funder of the FHI along with U.S. Forest Service and U.S. Endowment for Forestry and Communities. Then, if you look at the USEFC, you see that the main corporation involved with that is Enviva, which is the biggest biomass company in the U.S. South. You have to kind of follow trail; it’s not cut and dry.”

By combing through Powell’s funding reports, Petermann said she found that Monsanto — now owned by Bayer — Duke Energy, and ArborGen Inc., a biotech company in the business of trees, provided SUNY-ESF with 40.2 percent of its genetic engineering tree research funding between 2008 and 2017.

The fear, at least that of Petermann and the Melicans, is that the American chestnut — a nostalgic tree with grassroots loyalty and legions of aficionados — will become the Trojan horse to get genetically modified trees through the regulatory process and allow the companies that helped fund the research to create large-scale, artificially altered tree plantations.

“By taking advantage of the sentimental sweetness of the American chestnut, it opens the gate to legitimizing GE [genetically engineered] forests on an industrial scale,” Denis Melican said. “These companies would be clear-cutting areas as large as 100,000 acres, and plant GE trees in straight rows, and then in seven years, when they reach sufficient size, they would convert everything into biomass pellets for sale to the highest bidders.”

Genetically engineered trees have been a question mark dotting the pages of federal jurisdiction for years, with companies such as ArborGen peddling them as a carbon-sequestering, eco-friendly solution to the world’s energy needs — and they’re profitable, to boot.

“By investing now in the most advanced genetics available, you can ensure you will be covered no matter what happens in the timber market in the future,” according to the ArborGen website. “You will be prepared to sell anything from pulp to sawtimber — whichever is most profitable when you are ready to harvest. Our scientifically proven results & statistical data demonstrate without a doubt that when it comes to planting seedlings, choosing advanced genetics is the most sound financial choice you can make.”

Though touted as an environmentally friendly way to produce energy, GE tree farms, like many monoculture tree plantations, come with some major issues.

“Monoculture tree plantations, regardless of what they are, are very intensive,” Petermann said. “You’re growing a lot of biomass on a small piece of land in a very concentrated way. It depletes the soil and the water; it’s using up an enormous amount of nutrients, which means you have to put chemicals onto it — fertilizers, pesticides — to get the kind of growth that you want. You also need to be putting down herbicides so that the trees don’t have any competition. You want that tree, and only that tree, growing on that piece of land, so there’s no understory, there’s no other trees, nothing.

“In Brazil they call them ‘green deserts’ because there’s nothing else growing there.”

Two of the worst offenders are monoculture eucalyptus and pine plantations, whose flammable trunks and sap were the cause of deadly wildfires that ripped through Chile and Portugal in 2017.

While there will likely never be monoculture American chestnut farms — though they do make for great lumber trees — Petermann fears that the public will be coaxed into supporting a project that will blow open the doors for the growing of U.S. monoculture GE tree farms — and the problems they could create.

Powell dismissed this fear and maintained that his team is merely helping a revered organization restore a beloved tree.

“When you hear that there’s pushback, it’s really just a few small groups that have really big voices,” he said. “And I think most people realize that it’s not a for-profit thing; we’re not getting money, we’re not doing this to help out some industry or something like that. We’re just trying to get this tree back into the forest.”

American obsession

John Evelyn, an English writer, gardener, and diarist once wrote, “Chestnuts are delicacies for princes and a lusty and masculine food for rusticks, and able to make women well-complexioned.”

This is no less true today — minus the lusty part — in the sense that the American chestnut has fans from all walks of life.

“There are a lot of chestnut fans,” Federowicz said. “Everyone from teachers to history buffs to arborists to master gardeners to real-estate agents.”

Lovers of the American chestnut come from all backgrounds, beliefs, and places. From my younger brother, who almost burst at the seams when he found an American chestnut burr, to scientists hunched in laboratories for three decades in search of a way to save it, the American chestnut holds a place in our collective conscious that we are won’t to forget.

But has the obsession to save this one tree — when, as Petermann noted, the cause of the problem in the first place is the international plant and lumber trade — above so many other trees and plants and species, gone too far?

“Any of this work is kind of pointless, because forests continue to have new and unknown threats. Then, of course, climate change, so who knows what’s going to happen with that,” Petermann said. “So focusing on the existential threats to forest that exist right now, rather than trying to restore a tree that’s been gone for 100 years, seems to me to make a whole lot more sense.”

But for Federowicz, working to save the American chestnut, regardless of method, is a symbol of hope for our collective future.

“Who knows which approach will be best in Rhode Island versus Connecticut versus the mountains versus Maine,” she said. “There are all these issues, like climate change, that make it hard to predict. But I think there is hope, and one hopes there’s hope for humanity as well.”

Editor’s note: This story was updated Aug. 2.

If people want to see the details of what corporations and corporate consortia have backed the development of genetically engineered American chestnut trees, they can visit my 6 minute slideshow presentation: https://vimeo.com/377539143 — Anne Petermann

Monoculture tree farms and genetic engineering are separate issues, and conflating them is a fear tactic. Monoculture tree farms already exist. There’s no reason to think that genetically engineered trees would increase their use; in fact, if the trees can be engineered to produce more wood per acre, there would be fewer acres of tree farms needed.

Exactly. Not to mention that the hybridization process that is crossing and back-crossing American chestnut trees with Chinese chestnuts to get the blight-resistant gene into the American chestnut is also genetic engineering, it’s just a different type.

"GMO" has become a dirty word for many. How about Doctor, science, or hospital, these also are not natural occurrences. They are man made, I might add God inspired interventions. The American chestnut is gone if we don’t do something to help. Mr. Powell has a solution, it is done. There is a cure, but for the fears of a few this cure will not be implemented. What a tragedy, we have the cure for the American chestnut tree’s "Covid 19" and politics and nay-sayers will let the patient die forever. This is a tragic loss. We have the cure and can’t give the patient the medicine… so it dies forever. DON’T LET THAT HAPPEN!

There are pure American Chestnuts being bred for blight resistance. I wonder why they are never mentioned. There is no need for GMO or hybrids as pure Americans improve. There are always new pathogens, whether domestic or introduced. Do you continue to add genes? How many before the straw that breaks the camel’s back?