URI Looks to Tackle Mounting Plastic Pollution with Land-to-Sea Solutions

November 13, 2021

When early polymers were discovered in the late 19th century, they were seen as modern, innovative, pliable, and functional. The material, which would be developed into fully synthetic plastic in the 1900s, was heralded as a substitute for ivory, for stone and horn, for wood and metal. A material to save the environment, an equalizer of sorts, and the tool to launch the United States into an era of vast mass production and newly accessible material wealth.

Plastics were extraordinarily useful. But, as Judith Swift, director of the University of Rhode Island’s Coastal Institute, puts it, “the problem is that … we had no idea at the time just how extraordinary it would be.”

More than a century later, Swift noted “we have no choice” but to address the problem. Plastics today are found in the world’s most isolated places, most remote corners. They are ingested by species around the world, including humans. Each week, the average person around the globe consumes about a credit card’s worth of plastic, a 2019 study suggested.

“It’s run amok,” Swift said, plainly. “If we’re reaching a point where we’re actually ingesting plastic what possible choice do we have other than to address it.”

But there is no easy solution that will make plastics disappear.

“It’s complex in the fact that you and I can’t walk into a drugstore without buying plastic,” Swift said. “We can’t buy groceries without buying plastic. We can’t buy clothing without buying plastic. We can’t do any of these things.”

Plastic is the “only choice that’s being presented” to consumers, according to Swift. It has become so ingrained in society that there is no substantial alternative, no choice in the matter. This material entanglement on nearly every front means it is difficult to extricate the modern world from the problem.

It will take collaboration, innovation anew to solve the environmental and public-health problems being caused by the world’s overreliance on plastics. A new university-wide research network at URI hopes to do just that.

The Plastics: Land to Sea platform — a public-facing co-laboratories initiative and the “brainchild” of URI vice president of research Peter Snyder, according to Swift — will bring together nearly 30 interdisciplinary researchers to think holistically about the problematic polymer.

The endeavor features engineers, textile designers, economists, communicators, and biomedical and environmental scientists — “it’s literally a small army of individuals who are being gathered together to exchange ideas with each other,” Swift said. Together with nonprofits, other academic institutions, corporate partners, and government agencies, the initiative will try to figure out how to pull off one of the world’s greatest disappearing acts: drastically reducing global plastics pollution.

Images detailing the immensity of the plastics problem have long circulated, like those of the infamous Great Pacific Garbage Patch. But Arijit Bose, a chemical engineering professor involved in the network, said that is just the “tip of the plastic-berg.” Small plastic particles — between 100 nanometers to about 10 microns in diameter — have worked their way into water columns, he said, infiltrating the seas and being ingested into all sorts of marine life.

Bose studies the ways these microplastics interact with the smallest of marine life, bacteria, which are about 1 micron in diameter. He and his research team have discovered that when these bacteria encounter plastic nanoparticles, they bind to them. They try to “degrade the plastic or use the plastic as some kind of food,” he said.

“It’s very interesting,” Bose said, “because the implication for that is that maybe, maybe … the story’s not complete when we say we’re just dumping plastic and it stays in there forever and ever.”

Bose said he has long drawn on the expertise of other departments to figure out how plastics circulate in the ocean, the size of plastics observed in the water, and the chemistry of the plastic there — “all those things make a difference to our work.”

Formalizing and extending this collaboration through the research platform will help address the multifaceted, human-scale issue at hand, according to Bose.

“If research is done in silos, scientists may come up with potential solutions that work in a biological sense, but will not resonate with communities or decision-makers,” said Emily Diamond, assistant professor in URI’s Department of Communication Studies and Marine Affairs.

Interdisciplinary collaboration, she said, can allow for solutions that are “not only scientifically sound, but effective in society as well.”

Across campus in the Department of Environmental and Natural Resource Economics, assistant professor Pengfei Liu agreed.

“Economics cannot tell you how the plastic will affect the local marine ecosystem, right?” he said. “So, you need to rely on others and use the knowledge in other fields.”

His research focuses on how people value environmental amenities and resources, and the externalities imposed on those unattached to a line of production or consumption. With plastic, as with other resources and commodities, one person’s choices impact the welfare of others.

To solve this, market forces will play a hand, but Liu is adamant that education is key — that people will reduce their plastic consumption “not because it is expensive, but because they feel it is the right thing to do.”

For Swift, plastic has proved its value again and again — especially over the course of the pandemic. How could the world have coped without it, without the syringes, masks, nasal swabs, and vaccine packaging so crucial to COVID-19 response, she wondered. There is a reason plastic is so prevalent, there’s a reason it was seen as a “miraculous substance,” she said. But she is hopeful the URI initiative will help uproot that reliance.

“Plastic is the ideal thing,” Swift said. “But we’ve got to figure out some way to either develop it differently or to deal with the degrading process of it and the disposal of it in a way that isn’t going to be problematic.”

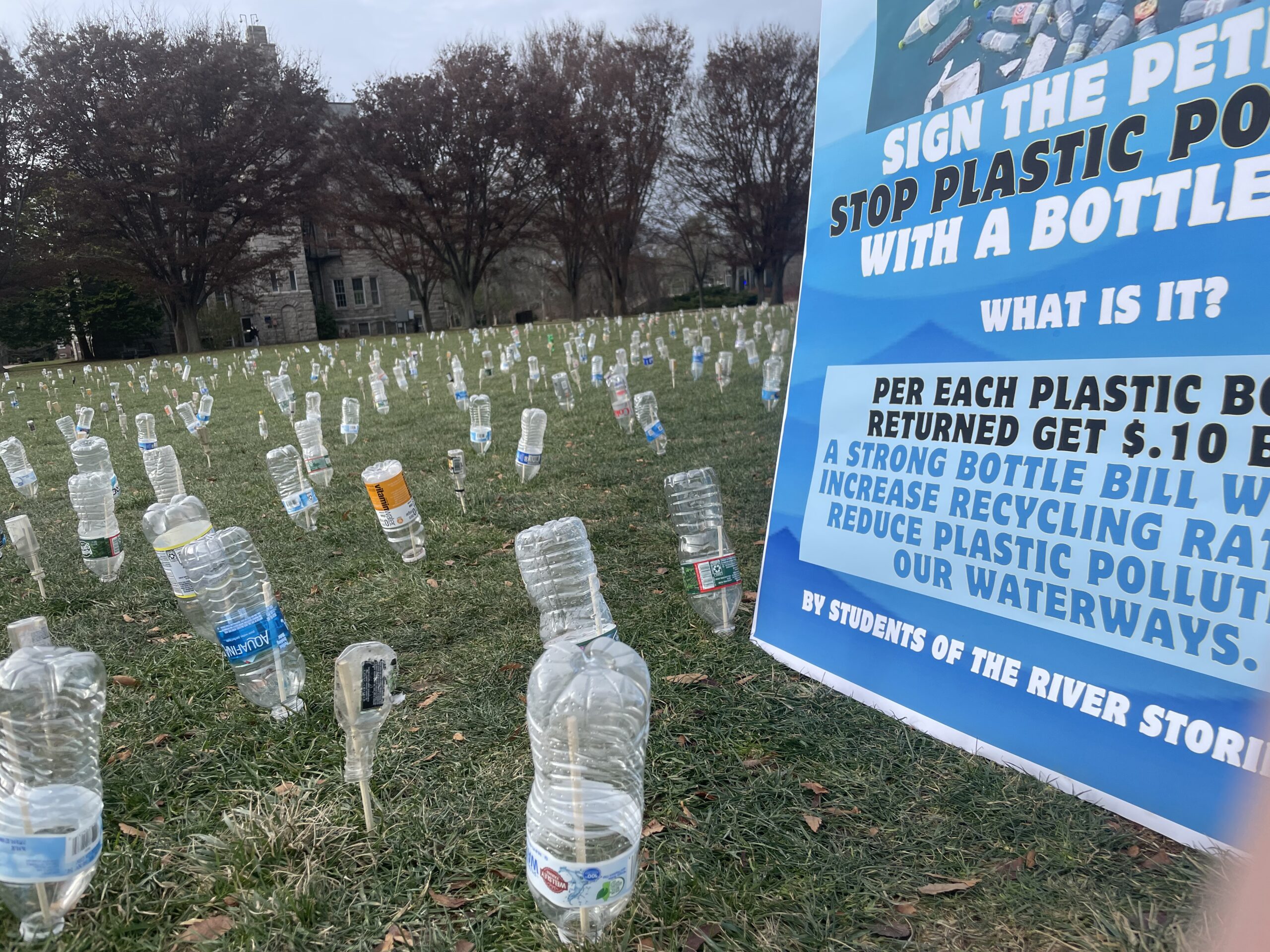

Rhode Island’s state legislature needs to develop and enact a single use bag and plastics ban for the entire state. They currently just leave it up to individual municipalities to do this. Any statewide legislation should also allow any town to adopt a more stringent policy if it chooses to. We are destroying our ocean ecosystem with this pollution.