City and State Debate 6-10 Connector Design

October 19, 2016

PROVIDENCE — The city’s planning department has veered away from the type of highway removal project it once championed as a way forward for the 6-10 Connector. It’s now proposing a limited-access “parkway,” dressed up with eye-catching automobile infrastructure, a handful of new over and underpasses that connect neighborhoods divided by the highway, and improved pedestrian and bike infrastructure in the surrounding neighborhoods.

In March 2015, the city held a well-attended community forum during which three invited guests, each an expert in the field of highway-removal projects, recommended tearing out the 6-10 Connector between Olneyville and downtown Providence, and replacing it with a multimodal boulevard. San Francisco’s Embarcadero, Milwaukee’s Park East Freeway and New York City’s West Side Drive were cited as successful case studies.

The quote from the night that stuck came from Peter Park, a former planning director for Milwaukee and Denver, when he said simply, “Remove a highway, improve a city.”

Highway-removal projects are generally understood to improve connections between neighborhoods, create opportunities for development on land previously occupied by the highway, and create more transportation choices for pedestrians, cyclists and transit users. The traffic nightmares regularly predicted by opponents of highway removal projects haven’t materialized in the growing number of case studies.

“There comes a point, from a policy perspective, where it makes sense for the (city) to have regional commuters driving on (its) terms, and not on some kind of long-distance commuting terms,” Ian Lockwood, a transportation engineer invited to speak at that 2015 forum, said.

While the city never explicitly committed to pursuing a highway-removal project, that forum specifically about such projects, along with a handful of subsequent meetings and presentations about the 6-10 Connector during which local officials encouraged the public to “think big,” implied the city would pursue a dramatic reimagining of the existing infrastructure. Instead, it’s pursuing another highway-speed, limited-access roadway that continues to divide the Valley, Federal Hill, West End, Olneyville and Silver Lake neighborhoods.

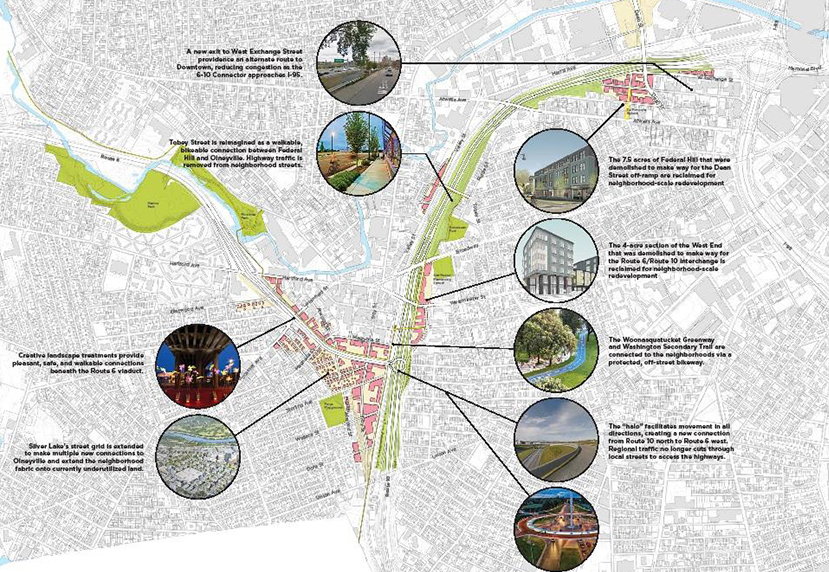

The planning department unveiled its scaled-down highway at an Oct. 3 public meeting. Specifically, the plan adds north-south connections under Route 6 between Silver Lake and Olneyville via Eastwood Avenue, Magnolia Street, Atwood Street and a new local road adjacent to the rail road tracks; one connection between the Federal Hill and Olneyville by replacing the Tobey Street on-ramp with a bridge for pedestrians and local traffic; and a pedestrian and bike bridge between the West End and Olneyville.

At each parkway crossing, the planning department promised a pleasant pedestrian experience, including bike lanes, sidewalks, street-scaping and public art.

The plan connects the Washington Secondary Bike Path to the Woonasquatucket River Greenway, a high priority for advocates of the state’s bike path network. Two separate connections, one logical for riders heading north to east or vice versa, the other logical for riders headed north to west or vice versa, would be made with separated bike lanes on local roads.

The plan also includes a “halo” interchange to replace the current 6-10 interchange near Olneyville. The halo would reduce the amount of needed infrastructure by combining multiple ramps into one piece of infrastructure, saving construction and maintenance costs. It would also allow drivers on Route 10 North to access Route 6 West without exiting the highway, alleviating through-traffic in Olneyvillle Square. This “missing move” is a major priority for many, except Gov. Gina Raimondo and Rhode Island Department of Transportation (RIDOT) director Peter Alviti who specifically didn’t include it in their proposed in-kind highway rebuild, though they said it could be added in the future.

While traffic would still move at highway speeds through the corridor, the city’s plan reduces the number of lanes between Olneyville and downtown Providence from three to two. The overall width of the highway would be reduced by up to two-thirds in places and exit ramps would be slimmed down. The smaller footprint would open as many as 50 acres of land for development. Most of this land would abut or be located near the high-speed parkway infrastructure; many lots abutting the existing highway are vacant or underutilized.

One advantage of the boulevard proposal, noted by the city throughout the 6-10 Connector debate, was that a Champs-Elyse-style, multimodal thoroughfare lined with mixed-use development could be created. The city’s latest proposed design seems to put an end to that idea.

Death of a boulevard

There was practically no mention of the boulevard idea at the Oct. 3 meeting. After the meeting, Allen Penniman, the city’s lead planner on the project, volunteered to ecoRI News that the boulevard option remained “on the table.”

“If folks really want the boulevard option, we need to hear that (the) design doesn’t go far enough,” he said.

But how the public should know to continue advocating for an option that the city no longer presents during its public meetings is unclear.

Developing a boulevard design for the 6-10 Connector is unquestionably challenging. There is a dramatic difference in elevation between the neighborhoods on either side of the highway, greater in magnitude than that of College Hill on the city’s East Side, according to Penniman. Additionally, the Northeast Corridor railroad tracks to the highway’s west must be crossed with bridges regardless of whether a highway or boulevard option is pursued.

Because of these topographic challenges, integrating the 6-10 Connector into the city’s grid of streets, as boulevard advocates propose, isn’t as simple as paving new streets across the highway. RIDOT has doggedly noted these constraints since Alviti spoke about the connector’s future at the 2015 forum. The city, meanwhile, acknowledged the challenges but resisted using them as a reason to discard options, such as a boulevard, until the early-October meeting.

From the start, RIDOT hasn’t favored the boulevard option. Initially, the state agency was willing to compromise between a boulevard project, which favors city priorities, and a highway rebuild, which favors suburban commuters, with a capped-highway proposal, similar to Boston’s Big Dig.

Then, just weeks after the U.S. Department of Transportation rejected a grant crucial to RIDOT’s ability to build this costly alternative, the agency abandoned compromise and requested that Raimondo fast-track an in-kind rebuild of the existing highway on the grounds that the deteriorating bridges were a public-safety emergency. The governor complied, giving an unexpected, no-nonsense press conference in August, which put an end to what was supposed to be a robust public input process on the future of the 6-10 Connector.

While the poor state of the existing infrastructure isn’t in question — its decade-old braces are now being held in place by braces of their own — the sudden elevation of public safety as a reason to fast-track the process is suspect. Before the grant application for the capped highway was rejected, the agency intended to maintain the bridges in their current state during a multiyear federal permitting process.

After the application’s rejection — and an additional city forum at which many residents demanded a major reimagining of the roadway — the governor suddenly declared she was “out of time.”

The city pushed back lightly. Mayor Jorge Elorza chose to appear alongside the governor at her highway-rebuild press conference, and agreed to end the city’s public input and design process for its own version of the 6-10 Connector early. He did insist that public safety and good road design weren’t mutually exclusive.

The governor made clear that a boulevard alternative wouldn’t be considered, and Alviti admitted that earlier discussions of the boulevard had only been a hypothetical thought experiment, as far as his agency was concerned, despite the public understanding otherwise.

The city continues to meet twice weekly with RIDOT about the project, but the terms of negotiation between the two have been massively shifted by the governor and RIDOT director’s hard-line stances. Past are the days when the city’s planning department asked residents to imagine a Champs-Elyse-style boulevard in place of the existing highway; now it’s asking residents to be enthusiastic about a “place-making” exit and entrance ramp on a rebuilt parkway.

Warm reception

While a boulevard project seems to have been considered the Holy Grail alternative by many advocates of reducing the negative impacts of the 6-10 Connector on the city’s divided neighborhoods, the city’s compromise plan has received a warm welcome, especially in light of the governor’s plan to rebuild the infrastructure in-kind.

Local resident Eric Weis, an advocate for complete-streets infrastructure, described the plan as “properly urban” and “doable,” and a good middle ground between the state’s intentions and the city’s priorities. Viewed on a spectrum, he placed the plan somewhere between a boulevard project and the state’s defunct capped-highway plan.

“The current highways fail every transportation mode,” he said. “The last thing we should do is put them back in place.”

Matt Moritz, board president of the Rhode Island Bicycle Coalition, said he is pleased with the plan to connect the Woony and Washington bike paths, and that the city’s new design addresses some of the congestion caused by the existing connector by allowing drivers to infiltrate the city’s grid of streets in more locations. He also noted that the city’s proposed parkway would be easier to convince commuters from Providence’s suburbs to accept than a boulevard would have, making it more likely to be implemented.

Alex Krogh-Grabbe, the coalition’s director, also describe the plan as a reasonable compromise. His endorsement was heavily influenced by the governor’s plan to rebuild the highway in-kind.

“RIDOT’s proposal to rebuild as is is patently absurd and asking for a (billion-dollar, taxpayer-funded) boondoggle,” he wrote in a recent e-mail to ecoRI News. “So, while the design presented by the City is pretty good in its own right, comparatively it’s amazing.”

Krogh-Grabbe was hesitant to endorse the idea of the pedestrian bridge proposed south of the interchange, fearing that it wouldn’t be executed or maintained properly, and noted that it would only be accessible from currently abandon frontage roads. He said he would prefer a protected bike lane alternative on one of the other crossings, such as Westminster Street.

Seth Zeren, of Fix the 6-10, said the city’s plan will help reduce overall vehicle miles traveled by restraining traffic to two lanes instead of three. Even if the fuel efficiency of the overall automobile fleet increases fourfold by 2050, he said, vehicle miles traveled will still need to be reduced by 50 percent to meet the state’s commitment to reduce greenhouse-gas emissions 85 percent by that time.

Art of the deal

The city’s proposed design marks its starting point in its negotiations with the state, making it naïve to assume it will get everything it has proposed. The city’s plan incorporates elements far outside of the project zone being considered by RIDOT. The state agency, now undeniable biased toward suburban commuters over city residents when it comes to the 6-10 Connector, could also refuse to surrender any existing lanes of highway capacity as the city’s plan proposes.

Penniman noted that the city’s plan could accommodate three lanes in either direction should that be necessary.

The highway- and budget-slimming halo interchange could also be refused by RIDOT, as it would force highway commuters to reduce their speeds when changing between routes 6 and 10 near Olneyville. The halo could also change the scope of the project so much that an environmental review process would be triggered — an outcome the state is specifically trying to avoid.

The Providence planning department is expected to release the final draft of its design in later this month at a public meeting. In the meantime, it’s determining the cost of the proposal — it’s expected to be less expensive than RIDOT’s rebuild alternative — and analyzing cellphone data it recently bought to determine exactly how many people are currently using the road, where they are coming from and where they are going to. That information should inform the city’s final design decisions.

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsRecent Comments

Leave a Reply

Your support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings

"The highway- and budget-slimming halo interchange could also be refused by RIDOT, as it would force highway commuters to reduce their speeds when changing between routes 6 and 10 near Olneyville."

I actually laughed out loud when I read that. As if the massive traffic jams the ineffective highway system causes now don’t already force people to reduce their speeds…