Impervious Cover Lets Runoff to Storm Ahead

May 25, 2010

Driveways, highways, rooftops, patios, parking lots and sidewalks cover 12 percent of Rhode Island. That may not seem like a lot of cement, asphalt and shingles, but these manmade impervious surfaces quickly funnel contaminated stormwater runoff into steams, ponds and rivers before the water has a chance to soak into the ground.

The impacts are devastating and far reaching.

Flooding, as Rhode Island witnessed earlier this spring, becomes both more common and more intense. Water tables drop and rivers, streams and wells fed by groundwater begin to dry up — see the Hunt River in Kent County as proof. Freshwater habitat is destroyed as sediment is sent downstream and surges of stormwater erode riverbanks and alter stream beds.

All that sediment that is hurried down rivers and streams by surging stormwater, for example, destroys the gravel spawning beds of native trout.

“Stormwater runoff from impervious cover obliterates habitat,” said Scott Millar, chief of the state Department of Environmental Management’s Sustainable Watersheds Office. “Who’s going to go out there and remove that sediment?”

In fact, since freshwater ecosystems are so closely linked to human activity — such as paving over open space that often destroys natural buffers —nearly half of the 573 animals on the U.S. threatened and endangered list are freshwater species, according to National Geographic.

Besides altering and destroying freshwater habitat, surging stormwater rushing over impervious surfaces — fertilizers, herbicides and pesticides also run unimpeded off lawns — collects and carries with it a host of vile pollutants that end up swimming in our waterways.

The most common disturbance in the chemical make-up of streams and rivers is elevated levels of nitrogen and phosphorous. Other common contaminants include calcium, sodium, potassium, magnesium and chloride from road salt. Runoff from impervious surfaces also contains metals such as nickel, chrome, lead, copper and zinc.

The only chemical that should be found in a healthy stream is dissolved oxygen.

“Nobody wants to go swimming or fishing in water that includes oil runoff and pesticides from lawns,” Millar said. “But that’s essentially what we are doing.”

About 75 percent of the stream miles that feed Rhode Island’s waterways with clean water are small headwater streams that typically are small enough to be straddled by a child. These streams, which are so small they often are not mapped or overlooked during development plans, are highly sensitive to land-use changes.

“These low-water streams often are ignored during the development process,” Millar said. “They are easily susceptible to contamination from stormwater runoff. These streams are feeding much of the clean water to the bay. We have no chance to clean up the bay if these streams are damaged. We can’t clean up our urban environment and at the same time ignore these streams.”

If the amount of impervious cover becomes too great in the areas where there are headwater streams, irreversible damage can occur to drinking water quality and aquatic habitat, according to a recently revised report entitled “The Need to Reduce Impervious Cover to Prevent Flooding and Protect Water Quality.”

The 20-page report, funded by the Providence Water Supply Board and the National Park Service, recommends keeping overall impervious cover below 10 percent, which will allow the land to absorb and filter runoff from developed areas and prevent excessive flooding, ecosystem impairment and contamination of water supplies.

“Water can’t penetrate these manmade surfaces,” said Millar, who edited the report that was written and researched by Dodson Associated Ltd., a Massachusetts-based landscape architect firm. “And there’s a lot of these surfaces in the landscape.”

As impervious cover increases above 10 percent, water quality begins to suffer, Millar said. When a landscape features 25 percent to 40 percent impervious surfaces, damage becomes severe; any percentage above that there’s a good chance any damage caused will be beyond repair, he said.

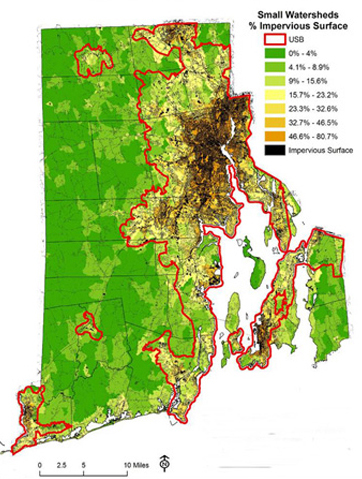

Most of the state’s impervious surfaces can be found within a 40-mile-long urban/suburban corridor along the shores of Narragansett Bay and in the watersheds of the Blackstone, Woonasquatucket and Pawtuxet rivers. Within this area, which the report refers to as the urban services boundary, impervious cover makes up 25 percent of the landscape.

Millar said it is important that Rhode Island keep future development within this already built-up corridor. The Exeter resident also said it is imperative that the state’s 39 municipalities adopt more creative land-use techniques and development standards that will guide growth away from sensitive areas, such as those that feature headwater streams, wetlands and woodlands.

Under natural forested conditions, only about 10 percent of precipitation runs off the surface, 50 percent soaks into the ground and 40 percent is absorbed by trees and other vegetation, according to the report.

As roads, houses and office buildings are built, this ratio starts to change, with runoff increasing as the amount of impervious cover grows. For example, the total runoff volume for a 1-ace parking lot is about 16 times that produced by an undeveloped 1-acre meadow, according to the report.

In fact, according to Millar, parking is a big issue when it comes to the amount of impervious surfaces that blanket Rhode Island.

“Everything is over-designed for massive pickup trucks and SUVs,” he said. “Build smaller parking spaces near buildings and offices for smaller cars. You can still drive those bigger vehicles, you’ll just have to park farther away.”

The DEM, the Narragansett Bay Research Reserve, Grow Smart Rhode Island and other organizations are promoting more environmentally friendly development practices, such as low-impact development, village development and conservation development. The DEM and Coastal Resources Management Council are even providing grants to cities and towns to encourage new development practices, Millar said.

The development practices that are being promoted avoid impacting sensitive areas and open space, minimize clearing and grading, use vegetated treatment systems, such as rain gardens and rain roofs, and protect natural drainage areas. These practices also call for mixed-use development, smaller lot development, narrower roads, getting rid of curb and gutter requirements and reducing or eliminating cul-de-sacs.

“There’s no reason to have a sea of asphalt at the end of a subdivision,” Millar said. “There are a lot of simple things we can do to decrease the impacts of stormwater runoff.”

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsYour support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings