Falmouth Homeowners Give Eco-Toilets a Try

Program meant to decrease nitrification of local estuaries

October 25, 2013

FALMOUTH, Mass. — Several years ago, local residents were suffering from sticker shock. They discovered it would cost $630 million to sewer 7,000 homes along Vineyard and Nantucket sounds, a move that would meet the state’s requirements for municipalities under the Massachusetts Clean Water Act but squeeze local finances.

“That’s the biggest project this town has ever taken on,” said local resident and former state representative Matt Patrick. “This would be enough to put somebody out of their home. That’s quite a bit of money, like doubling their property taxes.”

A new sewer system seemed the only option to deal with the issue plaguing Falmouth, and multiple other Cape Cod communities: the increasing nitrification of local estuaries. Once nitrogen invades an estuary, it acts like a fertilizer for aquatic vegetation, allowing it to spread rapidly and choke off sunlight to life below. This in turn kills eelgrass and invertebrate life, and makes the estuary, as Patrick said, “a stinking mess.”

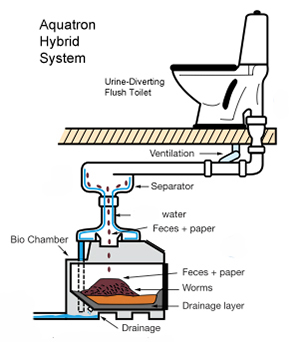

Patrick, who is the executive director for the Westport River Watershed Alliance, believed there had to be a cheaper and more eco-friendly way to meet the state’s demands. He spoke with David Del Porto, a Harvard University guest lecturer and expert in ecological wastewater management, about composting and urine-diverting toilets — widely used in Europe, Scandinavia and China, and in some the this country’s state and national parks — as a possible solution.

What he discovered was that urine-diverting toilets eliminated 80 percent of nitrogen and up to 60 percent of phosphorus and potassium from the waste stream. “It really is the perfect fertilizer,” Patrick said. “It’s clean and full of microorganisms.”

While still a state legislator, Patrick wrote columns in several local papers touting the benefits of eco-toilets. The idea was a hard sell. “I quickly became ridiculed in public,” he said. “It was pretty awful. People just thought it was a crazy idea.”

Town officials were less than supportive, but Patrick didn’t abandon the idea. With the help of Earle Barnhart and Hilde Maingay, founders of the co-housing community Alchemy Farm, he conducted well-attended workshops on clean water initiatives and, by the time the 2011 Town Meeting rolled around, he had reached enough residents who thought eco-toilets should be given a chance.

By unanimous vote, Town Meeting voters set aside $500,000 for Patrick and his team to pilot a demonstration project with volunteer homeowners. The money would subsidize eco-toilet installations up to $5,000 and pay for one pumping of a home’s septic system.

Patrick, Win Munro, a retired economist who had worked as an energy analyst in New York, and George Heufelder, director of the Barnstable County Department of Health and Environment, formed a working group to research the implementation of eco-toilets, They hired Sia Karplus, founder of Science Wares Inc., as a technical consultant.

The group sent out a letter with residential water bills requesting volunteers for the eco-toilet trial. About 160 people expressed interest. Munro and Karplus called each one, but Patrick said only a third qualified for home visits. Karplus then assessed each home to determine if an installation would be possible, depending on whether there was a basement, and which types of eco-toilets would be best suited for the space.

Turns out, eco-toilets aren’t one-size-fits all operations. Dry composting toilets use no water and require a direct drop system to a large composting box in the basement. Micro-flush systems can accommodate a 45-degree angled drop. Urine-diverting toilets separate liquid from solid waste and require space for an outside storage tank. And then there are vacuum-flush and foam-flush toilets, which use little to no water.

Karplus considers all these options during her visits and e-mails homeowners with information on which eco-toilets would be viable options, along with contact information for vendors. It’s up to each resident to choose a product and find a plumber for the installation.

So far, five eco-toilets have been fully installed, three homeowners are seeking permits from the Board of Health and five more have agreed to take the plunge. Karplus’ goal is to have 15 installed by the end of the year. She said the group wants to see how well the systems remove nitrogen before installing more.

Initial homeowner response has been positive, Karplus said, but “what happens as we get into the implementation is that … the actual particulars of eco-toilets are less desirable.” Homeowners may not agree on a system or like the idea of maintaining it. That’s when, she said, “they realize there’s a really big terrarium in their basement, and that they have to tend it.”

That doesn’t have to be a downside, though. Karplus said eco-toilet maintenance presents a great opportunity for the development of a regional facility that could collect compost, urine and food waste, process it into rich soil, and sell it to local farmers, landscapers and gardeners.

There’s also the cost factor. Retrofitting an eco-toilet to an existing structure is more expensive than installation in new construction. For homeowners whose existing system works fine, the price tag could be a deal breaker. For those whose systems need upgrading, an eco-toilet system would be a good bet.

Munro estimated that homeowners would have to pay $30,000 apiece to install a new sewer system, but only a third to half that for eco-toilets.

Eco-toilets are odorless, use little to no water and less energy, and facilitate the recycling of nutrients such as nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium found in waste. That last factor may be the most important for Falmouth, which must reduce the amount of nitrogen leaking into surrounding estuaries or face repercussions from the state.

To get a baseline for how much nitrogen and phosphorus eco-toilets divert, Heufelder will measure initial levels in participating homeowners’ septic systems, have the city pump them out, and then return for more measurements in the months following installation.

Munro said these measurements should continue until 2015, after which the working group will analyze the data to determine the average nitrogen removal per household and present its findings to the community. He hopes a decision on whether to further pursue eco-toilets could be made as early as 2017.

Falmouth may be the only municipality in the state — and possibly the nation — piloting such a program at the community level. “It’s a very big step,” Munro said. “In America, we’re on the cutting edge of introducing a new technology.”

Categories

Join the Discussion

View CommentsYour support keeps our reporters on the environmental beat.

Reader support is at the core of our nonprofit news model. Together, we can keep the environment in the headlines.

We use cookies to improve your experience and deliver personalized content. View Cookie Settings