Popular Insecticide Linked to Bee Die-Offs

Role of neonics in colony collapse disorder debated, but accumulation of poisons in the environment isn’t open for discussion

April 14, 2016

Natural pollinators, such as bees, birds, butterflies and bats, are responsible for nearly a third of the food humans eat. They transfer pollen and seed from one flower to another, fertilizing plants so they can grow and produce, say, watermelons or zucchini. Without these winged creatures, most notably honeybees, many plants and some 100 key food crops would disappear.

An increasing number of pollinators, however, are at risk of disappearing, according to a recently released global assessment. The two-year study, conducted by the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), found that both vertebrates, such as birds and bats, and invertebrates, such as bees and butterflies, are threatened.

The report noted that in some regions of the world, 40 percent of invertebrate pollinator species are so threatened by myriad environmental impacts that they’re facing extinction, with butterflies and bees representing the highest risk.

Threats to pollinators pose a considerable concern to worldwide food security, according to the IPBES. About 75 percent of all food crops require a pollinator to grow; nearly 90 percent of wild flowering plants depend on pollination by animals; and $235 billion to $577 billion worth of global crops are affected by pollinators annually, the report found.

The United States isn’t immune to the reported decline in pollinator populations. Between April 2014 and April 2015, U.S. beekeepers lost an average of 42 percent of their bees, according to various reports.

The relationship between the food people eat and pollinators makes the decline in the number of pollinators, particularly those of honeybees, concerning. In the United States alone, more than 25 percent of the managed honeybee population has disappeared since 1990, according to the Natural Resources Defense Council.

The disappearance of bees, often referred to as colony collapse disorder, is linked to a number of problems. Varroa mites and tracheal mites, imported accidentally to the United States from Asia in the 1980s, attack honeybees in all stages of life, from larvae to adulthood.

Here in southern New England, these two tiny pests are considered the biggest threat to the region’s honeybee population, according to local beekeepers ecoRI News has spoken with during the past several years.

These life-sucking parasites, however, are receiving human help in diminishing the pollinator population. Many commercial honeybees, for example, spend the winter dining on high-fructose corn syrup, not on their own nutrient-rich honey. It’s the equivalent of a fast-food diet. The loss of habitat and climate change are other factors.

There’s also the fact that the environment is awash in chemicals used to kill weeds, pests and fungi. Heck, the toxic pesticides specifically manufactured to kill varroa mites and tracheal mites are, in fact, poisons. These poisons don’t discriminate, and they’re use isn’t limited to industrial agriculture.

Kill bugs dead

Among the class of bug killers often cited by bee enthusiasts and environmentalists since the issue of colony collapse disorder first arose in 2006 are neonicotinoids, also known as neonics. Their use in the United States is prolific.

Neonics are a common category of pesticide manufactured by chemical giants Bayer, Dow, Monsanto and Syngenta. Rhode Island growers use them to treat apple trees, potatoes and pumpkins. Local turf farmers and tree-care specialists rely heavily on neonics for pest control.

Most of the corn planted in the United States — about 90 million acres of cropland — is grown from seeds treated with neonics. Nurseries and home gardeners also help spread one of the most widely used insecticides in the world.

The real impact neonics are having on bee populations, however, is topic of much debate.

Some studies have shown that the toxicity of neonics disorients bees, causing them to lose track of their hives. The Task Force on Systemic Pesticides claims some neonics are at least 5,000 to 10,000 times more toxic to bees than DDT.

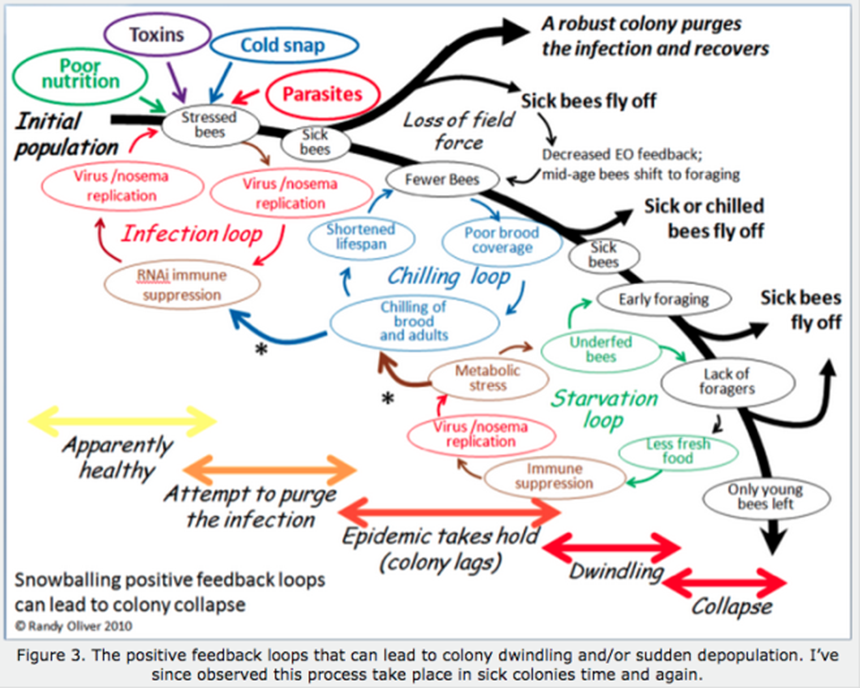

Others, including beekeepers and farmers, however, believe neonics are being unjustifiably blamed and targeted. They say the loss, and recovery, of bee populations is a complex system.

“The neonic issue is a very charged subject,” Randy Oliver recently told ecoRI News. “Unfortunately, much of it is based upon uninformed fear and misinformation. All pesticides need to be carefully regulated, but such regulation should be done based upon scientific evidence — not through political micromanagement of the EPA.”

Oliver owns and operates a commercial beekeeping business in California. With four decades of beekeeping experience, Oliver has become a well-respected expert on honeybee biology and beekeeping methods. He is an invited speaker nationwide, and runs the website ScientificBeekeeping.com.

He said there is no scientific basis for banning the use of neonics. “We’re caught up in a fear campaign,” the lifelong organic gardener said. “From an environmental standpoint, neonics are better than the more toxic chemicals the EPA is phasing out.”

As the use of neonics expanded in the commercial and retail sector, pressure to restrict their use prompted the European Union to enact a ban in 2013. There are no state bans in the United States, but a much-anticipated comprehensive review by the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) is expected by the end of the year.

Some studies have shown that bumblebees and mason bees are susceptible to neonics, and neonic planting dust from corn seeding can be a problem for pollinators. Despite those concerns and others, including suggestive evidence that neonics could be linked to premature queen failure and immune suppression, Oliver said neonics are the far more sensible option than, say, older pesticides such as organophosphates.

“Our agricultural system is too dependent upon pesticides. All of our pesticides are widely overused or used incorrectly,” he said. “No insecticide is without fault, and coating every single seed with neonics is stupid. But banning neonics would be a step backward. They’re the bridge until we get to the next generation of pesticides that will be better and less toxic.”

Oliver said he has spoken with beekeepers around the country and has been told that pesticides in general and neonics in particular aren’t a top concern. Their biggest concerns, he said, are varroa mites and viruses.

To ban or not?

In its first assessment on the risks posed by neonics, in particular the neonicotinoid insecticide imidacloprid, the EPA found that, among other things, the pesticide posed a greater threat to honeybees when applied to some crops rather than others. Corn treated with neonicotinoids, the federal agency found, poses less of a threat than crops such as citrus and cotton, which may have residues of the pesticide in the pollen at dangerously high levels.

Imidacloprid potentially poses a risk to hives when the pesticide comes in contact with certain crops that attract pollinators, according to the recent assessment.

The U.S. Fish & Wildlife Service, as of January, has stopped using neonics on public lands. The Maryland Legislature recently enacted a law, awaiting the signature of the governor, to ban their use beginning in 2018. Seattle and Spokane, Wash., and Eugene, Ore., prohibit the use of neonicotinoid-based pesticides on municipal-owned land.

Bayer, Dow and Syngenta have said neonicotinoids aren’t to blame for colony collapses and have stepped up lobbying to counter calls for bans. In 2014, Syngenta even petitioned the EPA to increase the legal tolerance for a neonicotinoid pesticide residue in several crops — in one case asking that the acceptable level be increased by 400 times. Neonics are a money-making products for the world’s chemical giants.

Lawmakers in several states, including Connecticut, Massachusetts, Alaska, California and New York, have introduced legislation in recent years that sought to limit or ban the use of neonics. None of the bills has yet to make it very far.

In Rhode Island, a recent Senate hearing highlighted support for the continued use of neonics. Heather Faubert, a researcher in plant science and entomology at the University of Rhode Island, testified at the hearing.

“There was a bit of hysteria thinking that neonics were causing (CCD) and there’s really quite a bit of evidence that it is diseases and varroa mites that cause colony collapse disorder,” she said. “If neonics were restricted or banned, I don’t think we’d see help to our bee population. I don’t think it would do a darn bit of good to help our bees.”

Little Compton farmer Tyler Young praised neonics for killing Colorado beetles and other local insects that threaten his potatoes and butternut squash. Pat Hogan of the Rhode Island Golf Course Superintendents Association testified that neonics are vital for grub control.

Regardless of their impact on pollinators, neonics, like the many other pesticides, herbicides and fungicides the environment is routinely doused with, are accumulating in nature.

More than 70 percent of pollen and honey samples collected from foraging bees in Massachusetts contained at least one neonicotinoid, according to a 2015 Harvard University study.